[ad_1]

Daniel Taylor has seen a sinister parade of illegal narcotics wreak havoc on local communities during his 17-year career in law enforcement.

First there was crack. Then methamphetamines and the opioid epidemic stole the show. But nothing could have prepared him for the recent arrival of the neighborhood’s strongest opioid, fentanyl.

“I worked a lot of different drugs,†said Taylor, a lieutenant in the Nez Perce tribe police force. “And this one scares me. That’s crack multiplied by 100.

Fentanyl is extremely potent, about 80 to 100 times more potent than morphine. Many people have only heard of it because of the overdose deaths of celebrities like musicians Prince and Tom Petty and actor Michael K. Williams. And while other parts of the country have struggled with the synthetic opiate for a few years now, it has only recently arrived in north-central Idaho and southeast Washington, according to Taylor and d other agencies involved in the fight against drugs.

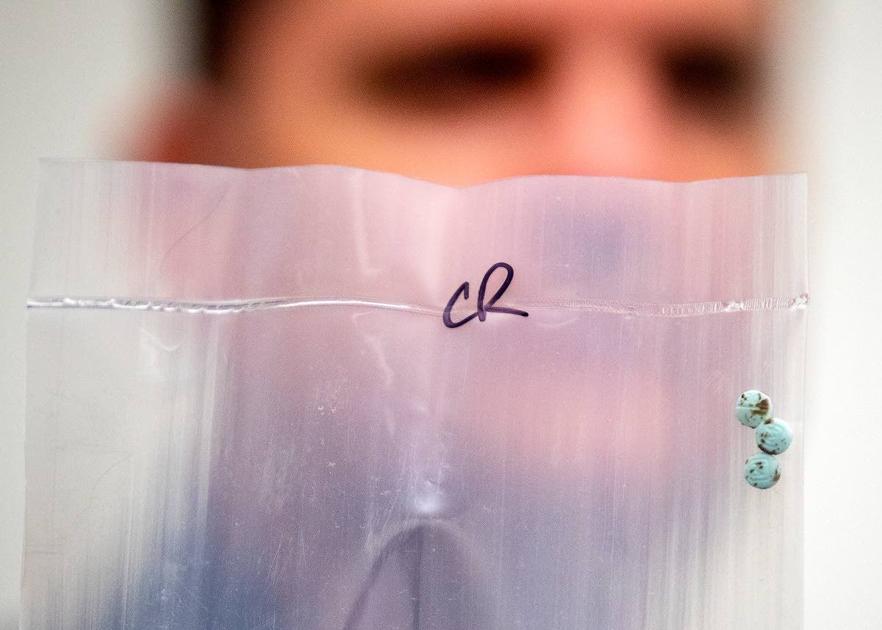

Hundreds of doses of fentanyl have been seized in recent months by various services. Most of them come in the form of fake oxycodone blue pills with a letter “M” stamped on one side and “30” on the other. They come from clandestine laboratories in Mexico, which has earned them nicknames like Mexis, Mexi 30s or simply “bluesâ€.

The problem has already become so serious on the Nez Perce reserve that authorities recently issued a public health alert to inform people about the appearance of the drugs and their associated paraphernalia. The tribe has also set up a task force to stay ahead of the coming wave.

“I’ve seen what crack does to people and a community, and I know it comes with those blues,†Taylor said. “I know it’s coming because I’ve been doing this for so long. We are up for it. Absoutely.”

Overdose deaths in Nez Perce County, attributed at least in part to fentanyl, have risen sharply this year, according to coroner Josh Hall. In 2018, there were no deaths. In 2019, there was one in Lewiston. In 2020, there was one in the department. But this year there have been five, including three in Lewiston and two in the county.

On reserve, Taylor has reported two overdoses and no deaths in 2019, four overdoses and two deaths in 2020, and four overdoses and one death this year. These statistics include two young women under the age of 20 who had to be resuscitated by an assistant with the opioid drug Narcan.

Taylor said his numbers are likely low, however, as police have only recently asked hospitals to start testing overdose victims for fentanyl.

Arrests are also on the rise, with three cases pending in Nez Perce County. One concerns a young woman from the Tri-Cities whom the police allegedly caught this summer with 200 fentanyl pills.

“All it took was that shot”

The tribal police took a different approach with the advent of fentanyl, mainly because it’s so easy to overdose and die from the blues due to the great variability in their dosages. So instead of just sending offenders to jail, officers worked hard to get users to rehab before it was too late.

One example is a young woman with whom Taylor worked personally, with intensive support from her mother. The Lewiston Tribune has agreed to keep their names private for fear of reprisal for speaking publicly about drug trafficking.

The woman said she started using fentanyl about a year ago, almost on a whim.

“My first thing was to take heroin,†she said. “I guess that wasn’t enough for me.”

A friend suggested that she try fentanyl.

“They said it would knock my ass off,†she said. “All it took was that shot, and I never injected heroin again.”

Soon her mother didn’t even recognize her anymore.

“She wasn’t really my daughter,†she said. “There is my daughter and there is this other person. It was bad. I didn’t like this person.

The woman had at least three overdoses, sometimes requiring the use of Narcan.

“Every pill is different,†the woman said, noting that she participated in the common practice of smoking the pills with a piece of foil. “You never know how much fentanyl you’re going to put in there. You never know when you are going to take that last shot with the pills. But once you get addicted, especially to blue pills, you don’t care as long as you get high or feel that rush. “

As little as 2 milligrams of fentanyl can be a lethal dose. According to an analysis by the US Drug Enforcement Administration, blue pills seized in Mexico contained between 0.62 and 5.1 milligrams, with nearly a quarter of the pills carrying a potentially fatal dose.

The woman said one of her main concerns now is warning children to stay away from pills because they look like candy.

“All it takes is for a little kid to get a pill, and they’re gone.”

Several law enforcement agencies in the area, including the Lewiston Police Department, issue Narcan to officers so they can save lives when they encounter an overdose victim. Sgt. Chris Reese, who has been the Lewiston Department’s K9 manager since 2009, said he’s started to see users wearing their own Narcan.

“They know there is a high probability that they will overdose, and so they take the necessary steps to take Narcan with them because they know the risk factor,†Reese said. “But because of their addiction, they don’t care. They always want to get high, even if that means they could eventually overdose and die from it. “

Agents have attempted to warn users that they are primarily playing a game of Russian roulette when using fentanyl.

“I have no doubts about it,†Reese said. “It’s only a matter of time before they get the wrong dosage, and they’re going to cash in.”

The tribal task force has launched a multi-pronged approach to tackle the increase in fentanyl abuse. Taylor said his main goal is to keep people from dying. Tribal health officials have launched a public education campaign that includes distributing doses of Narcan and training community members on how and when to use them.

Social media alerts and flyers all over the reservation, including schools, highlight images of the blue pills so people know what to look for. Police detectives were also tasked with training every division of the tribe in drug identification, including staff at the Clearwater River Casino outside of Lewiston. Particular emphasis is placed on the blue pills, the soot-streaked foil plates used to smoke them, and the telltale scent of burnt marshmallows due to the high sugar content of the pills.

Finally, there has been a change in the way the tribal police approach users who don’t traffic pills, Taylor said. Tribal leaders, police, prosecutors, health care providers and other members of the justice system are now working together towards a therapeutic approach to problem solving.

“This is new territory for our police officers,†Taylor said. “I think it’s important for people to understand that change is needed, and it will take this type of group effort to slow the damage this drug will inflict on a community.”

He said the change in policy had actually been refreshing.

“Tribal policemen have a closer connection with the people we serve,†he said. “It feels good to do like that. And I’ve been doing this long enough to know we’re not stopping our way out of this problem.

As the commander of the Quad Cities Drug Task Force, Whitman County Sheriff Brett Myers is intimately familiar with the illegal narcotics trade in the area. And like Taylor, he said a storm was brewing.

“I think we’re only seeing the first wave of this,†Myers said. “We saw maybe one or two cases two years ago, three or four last year, and then about once a month at the start of this year. But from May or June, it became a weekly event.

Overdoses have increased, he said, and there was one death this summer in Whitman County when a young woman died in Tekoa after using the blue pills.

The northwest interior is typically a year or two behind drug trends in more populous areas of the country, so it makes sense that the region has been spared the fentanyl outbreak for a while. time. But Myers said a steady increase in heroin use over the past few years, fueled by the wider opioid epidemic, has led users to turn to fentanyl for a more convenient and intense effect. .

However, recent moves to decriminalize simple possession have made enforcement and investigations more difficult. Those taken only with pills may face less serious misdemeanor charges, depriving the drug cops of hunting bigger fish.

“If a person just wants to be charged with possession of a controlled substance in Washington right now, it’s hard to get people to tell us where the drugs are coming from,†Myers said. “And frankly, if they say they don’t want to work with us, we have to find other ways to do it.”

He said investigators have been able to develop other methods to deal with cases up the chain. But the combination of what Myers called a lax drug policy with the wide availability of fentanyl is creating a perfect storm that’s about to engulf the region.

Addressing the problem on all fronts

The Nez Perce tribe is not the only entity preparing for the fentanyl surge. Idaho Gov. Brad Little traveled to the southern United States border last week to highlight concerns about the surge in methamphetamine and fentanyl overdoses from Mexico. Last summer, Little sent a team of Idaho State Police soldiers to the border to help with intelligence gathering and investigative work to keep drugs from crossing the border, according to the ‘Associated Press.

And last month, the Moscow City Council funded Police Chief James Fry’s request for a drug dog to aid his department in its growing encounters with methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl, substances that led to overdoses in the city.

“It’s not an aboriginal problem, and it’s not a white problem,†Taylor said. “It’s just a problem of everything. We call it shoveling sand with a fork. We will eliminate a trafficker, and maybe even an organization, and in two or three weeks there will be another in place.

[ad_2]